For Black History Month, the Law Library will spotlight Black law figures throughout history and their contributions to the legal field. Each week, a different figure will be featured.

by Sydney Hamilton, 1L

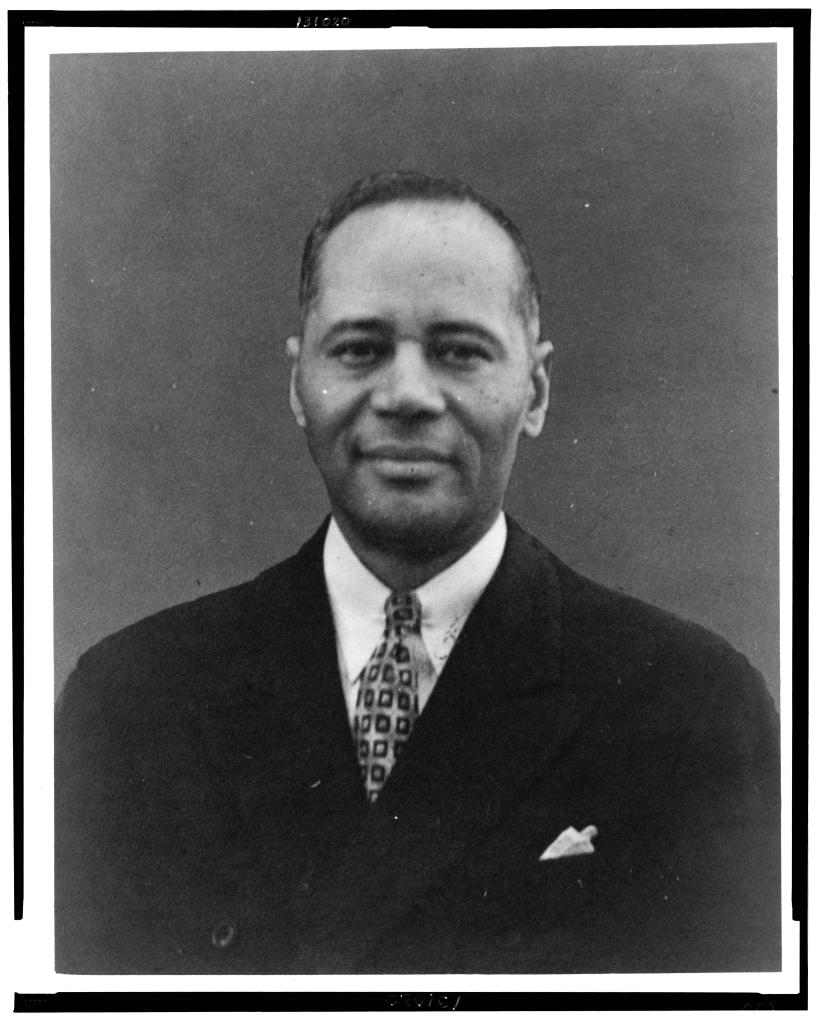

Charles Hamilton Houston in undated photo taken sometime between 1940-50. Photographer unknown. From the Library of Congress NAACP collection of portraits of founders, board members, staff, branch officers and other prominent cultural, social and political figures. LOT 13074, no 249 [P&P].

Charles Hamilton Houston (September 3, 1895 – April 22, 1950)

Born in Washington, D.C., Charles Hamilton Houston first encountered the legal field through his father, a hard-working attorney in the nation’s capital. However, his father’s exemplary career did not solely inspire Houston to go down a similar path. After graduating from Amherst College and teaching at Howard University, Houston enlisted in the military when the First World War began. During this time, Houston experienced tremendous racial discrimination. He came to a bewildering epiphany: he served a country that did not even value his life and scorned his existence. “I made up my mind,” Houston once said, “that if I got through this war, I would study law and use my time fighting back for men who could not strike back.”[1]

Houston returned to the U.S. in April 1919, the beginning of a period now called the “Red Summer.” This period of violence resulted from several events. For one, the war had further encouraged the Great Migration, a mass emigration of Blacks to the North and the Midwest from the South, seeking to escape increasing racial violence and find better job opportunities. At the same time, the veterans were returning home from the war. This led to a flurry of emotions and opposing attitudes. Many White veterans and civilians were upset about Blacks “taking” jobs that Whites felt rightly belonged to them. Additionally, Whites feared that many of the Black veterans, now equipped with more experience and military training, would no longer allow themselves to be subjected to the racial status quo established in the U.S. On the other hand, many Black veterans were returning from foreign countries where they had been treated better and resented coming home to a country that did not appreciate their service. These rising tensions culminated in some of the bloodiest riots in American history, the worst occurring in Elaine, Arkansas, where at least 100 Black Americans were killed. However, this was notably one of the first times in U.S. history that the Black community had collectively fought back against racial violence.

These events colored Houston’s law school education when he entered Harvard Law School. While there, Houston became the first Black student elected to Harvard Law Review’s editorial board. He later obtained a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship, which allowed him to study at the University of Madrid and earn a Civil Law degree. After graduating, Houston returned to Washington and joined his father’s law practice, one of the first Black law firms established in D.C.

A foundational tenant of Houston’s approach to the law was the importance of defending and protecting the Black community. He felt that Black lawyers had an obligation to argue on behalf of their community because White lawyers could not be depended on to fight against racial injustice. Eventually, Houston began teaching part-time at Howard Law School and was appointed vice-dean in 1929. In his new role, Houston made it his mission to turn Howard Law School into a “training ground” for future civil rights lawyers, such as Thurgood Marshall. Before long, Houston turned the law school into a formidable institution, helping them to attain accreditation from the American Bar Association.

In 1935, Houston left Howard to work as the first special counsel for the NAACP. Houston’s main objective was to diminish and eventually abolish Jim Crow laws, which he did through his arguments in several civil rights cases. However, Houston’s most impactful contribution was his strategy to debunk the “separate but equal” myth from Plessy v Ferguson (1897). He first used this tactic in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1939), arguing that it was unconstitutional to prevent a Black applicant from attending a law school “when no comparable facility for Blacks existed in the State.” Winning that case proved the effectiveness of Houston’s ingenious approach.

Houston’s efforts officially paid off in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), when the courts declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Unfortunately, Houston passed away four years earlier, in 1950, before seeing the fruits of his labor. However, his pupil, Thurgood Marshall, made the winning argument in the case. So, perhaps Houston’s spirit was present that day.

[1] “Charles Hamilton Houston.” Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, legacyofslavery.harvard.edu/alumni/charles-hamilton-houston. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

Other Sources:

“Charles Hamilton Houston.” Separate Is Not Equal: Brown V. Board of Education, americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/3-organized/charles-houston.html. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

“Charles Hamilton Houston.” NAACP, naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/charles-hamilton-houston. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

“Long Road to Brown: Cases and Lawyers: Charles Hamilton Houston.” Beyond Brown: Pursuing the Promise, www.pbs.org/beyondbrown/history/charleshouston.html. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

“Red Summer: The Race Riots of 1919.” The National WWI Museum and Memorial, http://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/red-summer. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

“Racial Violence and the Red Summer.” National Archives, http://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/wwi/red-summer. Accessed 18 Feb. 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.